Today, cruising evokes images of leisurely tropical destinations or exploration of historical sites on another continent. Not long ago however, traveling by passenger ship was transportation, and speed mattered. The need to quickly cross the Atlantic, combined with a geo-political climate (including two world wars) that promoted national pride, lead to government and industry joining hands in the quest for a symbolic award: The Blue Riband.

The Blue Riband wasn’t an official award issued by any state or company, but something every ship operator wanted in a bid to win passenger traffic, while nations wanted it for the prestige.

A total of 35 Atlantic liners held the Blue Riband for some time, but few for very long. From 1845 to 1952, the ship to hold the record for fastest average speed across the Atlantic was Cunard’s Mauretania, reigning from 1909 to 1929. The race for the award, whether by stoking competition or merely as a side effect of it, saw millions of emigrants transported, cultures changed, and even wars shortened.

Let’s dig into why this accolade was once so celebrated, and why it’s since faded away.

Note from Billy: There is so much to discuss with regard to the history of ocean liners, but I tried to stick to the Blue Riband. Advanced apologies for any tangents you’re about to read through.

The Only Way to Cross…For a Time

Necessity drives markets, and in a time where Guglielmo Marconi’s radio-telegraph began shrinking the world, so too was needed a way to shrink travel time. There were no transatlantic flights, and certainly no Facetime or Skype calls closing gaps, so the need was placed entirely on the shoulders of one industry: passenger ships. No matter if you were traversing the Atlantic for leisure, for business, or to emigrate, it was, as John Maxtone-Graham’s book notes, “The Only Way to Cross.”

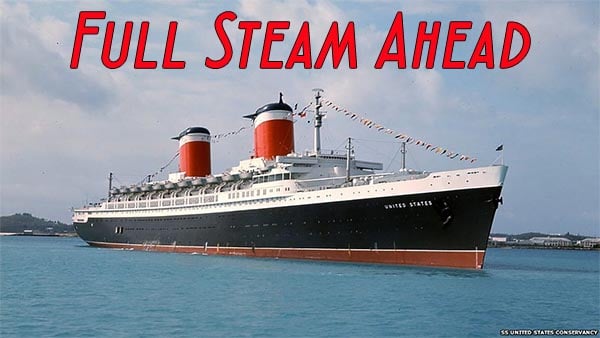

The first crossing of an iron-hulled screw-driven passenger ship took place with the 322 foot-long Great Britain in 1845, which made it across the Atlantic in 14 days and 21 hours. Speed and luxury continued to improve while ships dominated Atlantic travel, but of course as airplanes began taking center stage, allowing passage in hours, not days, the prestige of a fast ocean liner quickly faded, and the last holder of the Blue Riband was the SS United States in 1952.

The Evolution of the Great Liners

It’s easy to look at ocean liners of the past and focus on the grandeur and opulence enjoyed by those fortunate enough to experience such things, but a big part of what made these liners bigger than life was their physical size and speed. Early liners were egalitarian in their limited accommodations, relative to later builds. Even today, ships remain among the largest moving objects created by man, and on the heels of the industrial revolution, ships like the Great Britain were marvels of modern engineering despite rough rides, bare accommodations, and little privacy.

The Golden Age of ocean liners came in 1897, when German shipyard, Norddeutscher Lloyd, launched the 14k gross registered ton (GRT) SS Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse. She and her sister ships not only managed to win the Blue Riband from the British, but they did so with the most luxurious accommodations at sea. She was also the first ocean liner built with four funnels. Interestingly, she only needed two funnels, however more funnels gave passengers a feeling of safety and power – a tradition that has carried on even into the 21st century with Disney Cruise Line, Holland America Line, and others. While the Blue Riband was still about speed, it quickly became essential too, to provide opulent accommodations and public spaces – evoking imagery of dominance.

Germany continued to offer luxurious and fast liners, but the British dominated in size. Interestingly, many British liners were ships of state. Cunard’s Lusitania and Mauretania, launched in 1906 and 1907, were built with the promise of a £150,000 annual subsidy and a £2.5million in a low-interest loan from the British government. While national pride was indeed an incentive for the government to help Cunard build these liners, there was more to the arrangement. The terms? The ships would be available for conversion to armed cruisers when needed by the British Navy. While history isn’t always crystal-clear, the Lusitania, later sunk by a German U-boat, may have paid the highest of prices for this agreement.

Many stories persist to this day that one of the most unfortunately famous liners, White Star’s Titanic, may too have fallen victim to hazardous action in a quest to win the Blue Riband, but she, and her sister the Olympic, were vessels specifically built for luxury, and not speed.

The Germans, British, French, Italians, and the Americans all spent decades building more advanced ships capable of faster crossings. The introduction of diesel fueled engines, instead of coal, as well as many design changes based on trial and error, all continued the race to be the fastest.

Eventually liners begin to resemble what we are familiar with today, arguably beginning with the 81k GRT Queen Mary in 1934. This fast and elegant pride of the British people held the Blue Riband, intermittently, for 15 years until 53k GT SS United States stole the prize in 1952, averaging 35.59 knots. While technology had evolved, it was still a surprise at the time as the US had struggled to find success in the world of passenger ships dominated by the Europeans.

A Transforming World Took to the Sky

Unfortunately, the SS United States would be the last ship to be awarded the Blue Riband, not because she couldn’t be beat, but because by 1952 transatlantic air service had put a significant dent in the business of ferrying people across the Atlantic. The airship entered service in the 1930s offering smooth crossings in two days, and as fixed-wing aircraft evolved with turbo-props and eventually jet-engines, there was no competing if the goal was simply transport.

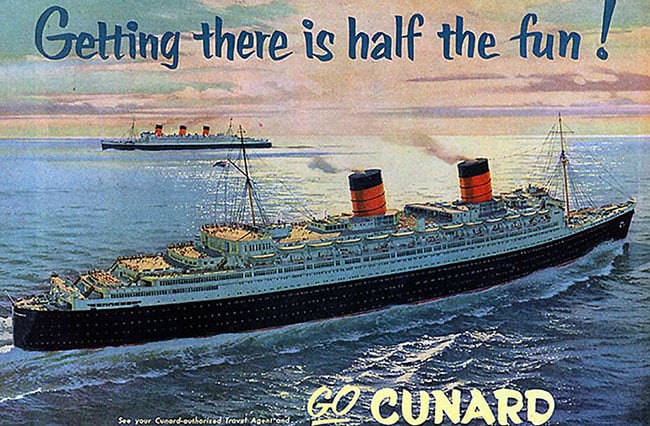

Cunard Line made two interesting attempts to stay relevant however, one more successful than the other. In 1960, as Cunard struggled to find profit in Atlantic service, they even purchased 60% of British Eagle, an airline, which they then named Cunard Eagle Airways. The effort was short lived through as the name wasn’t enough to differentiate them in a rapidly growing field of competition, though they did later begin a long-standing relationship with British Airways, promoting crossings on the Queen Elizabeth 2 with supersonic travel on the Concord - the two fastest ways, in their respective categories, of crossing the Atlantic.

Where We Are Now

Cunard’s other attempt at saving passenger service at sea was much more successful, and lead to a commonly used expression. The company launched an advertising campaign with posters, billboards, and even a film, reminding potential passengers that, “Getting there is half the fun.” It seems while their business transformed, they were ultimately correct.

Many factors have come together to create the cruise industry we know today, and we now sail for very different reasons. Often, we strive to enjoy more days at sea, rather than racing to a destination, because the ship has so much to offer and there are certainly faster ways to get anywhere we want to go. Transatlantic crossings are often incidental today, billed as "repositioning cruises," ranging from six days to two weeks, and the majority of the 20 million cruisers in 2017 stuck to the warm waters of the Caribbean. In this way we no longer race for the Blue Riband but lines race to outdo one another in size, novel features, stunning design, and more. Modern cruise ships rarely sail more than 25 knots. These things aren’t always as easily measured as speed, but much like the Blue Riband they drive the entire industry, even though not every vessel or line is competing in this way.

The diverse options that cruising now represents will hopefully mean a long life for the cruise industry, and continued enjoyment for those who look to the sea, as no single milestone dictates the industry, and it’s not likely that any single advancement will cause its rapid decline. After all, when the ship is the destination, getting there is more than half the fun.

Do you love ocean liner history - or do you simply love what it has brought us? Want to know more (we could go on for days)? Comment below, or reach out on Facebook or Twitter.